This isn’t about how all religions are very nice chaps, really, or that–ideally–all religions promote peace on earth, good will toward men, and women, in their own very different ways. Not even the religion that copyrighted that slogan in the New Testament after stealing it from Virgil’s fourth eclogue (where it’s assigned to the Muses of Sicily) has been able to follow the advice of the angel choirs.

No, this isn’t about how religions are greatly misunderstood by nearly everybody who feels less than passionately about religion, how they inevitably fall short, like David the King, of what they really and truly and essentially are. I have no idea what any given religion essentially is and much less an idea what religion in general essentially is. I have theories, of course.

But I do know that religion is slippery when confronted with its sins–ranging from blowing up fellow worshipers or abusing children in rectories and laundries, to grabbing one more snip of land before “peace talks” (I love the phrase: so standard we overlook how insipid it is) can resume in Israel. Convenient too that any “religion” can say (with deference to the greatly overrated and entheogenic Huston Smith), “You must mean the other man’s [sic] faith.”

Religion alone seems able to convince ordinary people that there is no point at which abuses and sins become definitive and not exceptional: imagine judging a serial rapist by saying that he’s simply failing to live up to his ideals and that, for all appearances, he’s really a very nice chap.

Down with ideals and on to concrete proposals in this tenth year in the third millennium of the reign of Our Lord Jesus Christ awaiting his long delayed coming. (What did you think AD meant?).

It is time for a list of things religions must give up, forswear, abandon and forever repudiate in order to be what they want to be–or say they do: mechanisms of peace, justice, compassion and love of humanity.

Christianity

1. Abandon the mythology of Genesis. God did not make the world in 6, 8 or 1000 days or 1000 days of years. Stop squabbling over Hebrew syntax and what you think the Biblical writers meant. They meant what they wrote and they were wrong. We know far too much about how things really came about to believe any of the nonsense written by a Hebrew-speaking priest of the sixth century BCE who thought things came about by a direct act of his hereditary deity.

2. Abandon any suggestion that you are doing science when you teach creationism. “Mysteries” are not taught in schools. Science is not about the unexplained but about the way we can best explain things. If you want students to learn about creationism, teach it in a junior year mythology class alongside Greek and Roman literature.

3. Stop trying to convert people. Do you hear me you evangelical jabberwockies? Yea, the day is coming–yea it approacheth, when the converts will stop listening because you have no idea what you’re talking about and no one in Malawi can eat the biblical bread you promise when the maize crop fails again.

4. To Our Catholic Brothers and Sisters: Abandon the liturgy you stumbled into in the 1960’s. It sounds like the 1960’s. If you must continue it, make your priests wear balloon-sleeve transparent yellow shirts with flouncy cuffs, paisley ties, and flare-bottom jeans. Maybe a striped pancho for special feasts. If you sound like an era, look like an era. And also with you.

5. To the Anglicans: Good job of putting all divisive theological issues aside, especially those based on that uncooperative tome called the Bible. Now stop counting theological success and rectitude in the number of gay and lesbian bishops you ordain, admit you’re agnostics who like to dress up and have a good time with it.

6. To all fundamentalists: Blessed art thou among Christians, for even though you will surely not see God and the Kingdom, and even though your personal morals are as shoddy as everyone else’s, you probably really believe what you say. Now, go back to school, learn a little science, and take a little wine for thy stomach’s sake. Oh, and please stop mucking up the airwaves with your prayers and singing and sales pitches. It keeps me from watching the real shopping channels–the ones where I can actually order something that comes in a box, something that I can really be disappointed with when it doesn’t fit.

Muslims

1. Give up the idea that the Quran is the most beautiful poetry ever written, the most perfect Arabic ever set to ink, the closest we can approach God in the scheme of time. Are you inhaling this stuff or just smoking? You have two hundred poets whose Arabic is better, any one of which could have won in a slam-down with Gabriel.

2. For all I know, Mecca is a lovely place. But get a second archaeological opinion on the Kaaba and especially that Neolithic outcrop, the jamarat, where people get trampled to death every year at the Haj trying to throw one last stone at the stone devils before curfew tolls and they have to board the bus. (Most recent tragedy, 2006: a stampede killed at least 346 pilgrims and injured at least 289 more.) –-Better now that the pillars have been hidden from view behind a wall, but still a pretty dubious ritual. My suggestion: learn to throw rocks at your politicians and hateful, firebrand illiterate mullahs who keep you from being nice chaps, really.

3. Let your women get an education. Admit that the most ordinary housewife who chooses to wear hijab to keep her husband and eldest son happy is smarter than the average imam. Don’t cut off people’s legs for adultery. Stop the stoning. Stop saying that cliterodectomy is un-Islamic, or rather shout it out and mean it. Don’t throw battery acid in girls’ faces for consorting with boys en route to school. Stop torching the schools.

4. If you think everyone in the religious world is evil and that you alone possess the key to truth, maybe a nice debating club would provide sufficient technology and less loss of life than your current plan. You really are making a lot of enemies this way—I have to be honest.

5. Stop promoting fallacies and false history. Medieval Arabic science was truly remarkable. Philosophy and medicine especially, and physics, not to be sneezed at. Now teach the real reasons the Islamic star ceased to shine brightly–dynastic feuding, internecine violence, a vilification of secular and scientific learning that continues today–and no fair jumping ahead to the Crusades or the colonial period for your answer. In general, the crusaders were far too stupid to pick up anything along the route to Jerusalem except diseases and by the time colonialism comes into view Islamic learning had been in eclipse for five hundred years.

6. Stop whingeing about how people who “blaspheme” or defame Islam are the “source” of violence within Islam. Here is a cart.

Notice that the horse is different because the thing on legs pulls the thing on wheels. Is this analogy unclear? See 5, above re: learning.

7. Stop blowing yourself up and calling the killing of your friends and neighbours “martyrdom.”

Nobody else is doing this. You are. In general, I don’t have an opinion on the wisdom of cultivating religious doctrine through suicide bombing, but I tend to think it’s counterproductive and immensely stupid, don’t you?

If the early Christians had tried this against their pagan persecutors in the marketplaces of the Roman world there’d be no one left to tell their story. If this had been the tactic of the medieval bishops against the heretics and Jews, guess who would have come out on top?

Judaism

1. There are no chosen people. There are just people. It is depressing, isn’t it? We all want to be special.

2. Stop trying to sell archaeological crap to the gullible west and Alabama Baptist yokels. You did not find Jesus’ family tomb. You did not find a neighbour’s house in Nazareth and probably not even Nazareth (Show me the city limits sign). I know that $1,000,000 comes rolling in every time you get a story on the cover of Newsweek, but you and I both know that this schlock is going to be available at Remainders ‘R Us a year from now when no one is looking.

3. Do your construction teams ever take a vacation? If I had been raised to think (as every Palestinian has been raised to think) that Israeli bulldozers are as aggressive and hateful as tanks I might see you as invaders and occupiers. I know you need to find room for the swimming pools (God wouldn’t want his chosen people wandering around in a desert, now, would he?), but give it a rest.

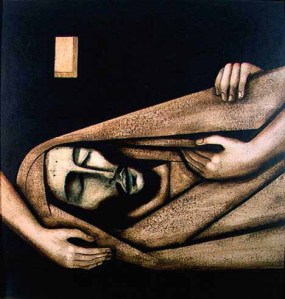

4. I know I will be slapped for saying this, but you really must get over the Holocaust. Yes, of course, I believe 6,000,000 Jews were slaughtered for no reason except their beliefs. Yes, I believe it was the greatest sacrilege against humanity of the twentieth century, not counting Hiroshima. But I think the best guess is that between 62 and 78 million people died in World War II, and in one way or another all were victims of the same racist ideology. Perspective is always nice, and at some point you will need to confront the fact that history is unkind to the monuments of persecution and tragedy. At a certain point, the cry for justice sounds a lot like the God of the Bible who screams for revenge.

5. Stop winning so many Nobel Prizes. It’s so embarrassing it’s not even funny. But your comedians are.

And to All?

1. All of you need to relinquish belief in heaven, hell, eternal reward, and eternal punishment. And of any God who participates in such abusive game-playing. These things do not exist except in your head. To the extent any of your conduct–towards virtue or towards killing infidels who don’t agree with you–is motivated by eschatology, you are living a dangerous fantasy and teaching your daughters and sons it is true.

2. All of you need to grow up a little. Some religions more than others, some people within each tradition more than the rest. It’s no wonder that some of our best minds since the nineteenth century have compared religion to infantile delusion and childlike behavior. Sorry to say, most of the people who see religion this way have been semi-believers or unbelievers.

But who’d deny that the Taliban behave like two year-olds with guns rather than like men, whether they are beating girls or blowing up Buddha statues in Bamyan. The robust beards are only masks for the deep sense of masculine insecurity they mistake for obedience to God’s will. Their wives will know better.

3. Value secular learning. I do not know whether the truth will make you, or me, free. I do know that religious truth is normally a shortcut for the intellectually lazy, crafted and sustained by preachers who like one-book solutions to the manifold problems of a complex world. There are no one book solutions, and if there were, they will not have been written in antiquity.

Both the Bible and the Quran have served that purpose in their time. ButTruth in the sense religions try to frame it–as dogma or superior knowledge–isn’t worth a confederate dollar. Knowledge of history, science, and the things of this world will get you a lot farther down the road to true salvation than religion will. Embrace it.

4. Don’t rely overmuch on “interfaith dialogue,” the corporate certainties of the religious world, the merging of fantasies in favour of a grandly mistaken worldview and the substitution of “dialogue” for serious reflection and discourse. As religions grow less confident in the twenty first century, at least in terms of their ethical and explanatory value for human life,they will turn again to the arena of martyrdom as a proving ground for faith above reason. Do not be fooled.

Postscript on the Holocaust, December 29, 2009

I knew I would be held to the fire for using a phrase like “get over” in relation to the Holocaust. I have been. What I meant of course is that the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of holocaust victims and survivors will not be able to sustain the horror of the event: history erodes not only the intensity of a moment but often its significance for people born long after the moment is past. Jewish friends and relatives agonize over this very pattern; it is a loss of sensitivity familiar most of all to Jews. I am worried that creating an idol of horror-of making the holocaust a religious symbol rather than a human catastrophe (in part, of course, religiously-motivated and supported and with a long history in European civilization), will make it transcendent and incomprehensible. Hollywood and holocaust-themed memorials and museums may play a useful role in pricking memory and consciousness, but their proliferation also betokens what the historian Robert Hewison once called the “imaginative death of reality.”

Human beings did this. It has to be come to terms with at the human level and not preserved as another idol of the tribe. “Getting over” is not the best way of saying “come to terms with, comprehend, move forward,” but that is what I meant.